Neck Wall Thickness

The first consideration, is the thickness of the newly formed case necks. When a case neck is reduced in diameter, or moved during case forming, the wall thickness increases. Brass cartridge cases are progressively thicker as you approach the base. This means that when a new case neck is formed from what was previously the parent case's shoulder or body, the neck wall thickness will increase. This can create a dangerous condition if there is not adequate clearance between the neck of the loaded cartridge and the chamber. This clearance can be determined by comparing the measurements of a dummy loaded cartridge and the neck diameter of your chamber. We recommend a minimum clearance of 0.003". If you do not know the neck diameter of your chamber, you should enlist the aid of a competent gunsmith to assist with the project. He will undoubtedly take a chamber cast.

The "Donut"

The second consideration is the formation of a "donut". This is a ring of thicker brass inside the neck of the newly formed case. The donut appears when the neck-shoulder junction of the newly formed case ends up closer to the base than the parent cartridge. This donut must be removed or dangerous pressures will result due to the lack of clearance for the case neck to release the bullet. Again, we recommend a minimum clearance of 0.003".

Neck Thinning

There are two common methods used to reduce the neck wall thickness of cases and remove donuts from their necks. The simplest is neck reaming. Reaming can be performed on a case trimmer or in a special reaming die. The die method is preferred, as the reamer tends to follow the off-center hole in the case neck when reaming on a trimmer.

The preferred method of thinning case necks is to use an outside neck turning tool to remove brass from the outside of the case neck. If the neck turning operation is performed one or two calibers larger than the final desired caliber and a size button is pulled through the neck, it will also remove the donut from the case neck. Neck turning produces a more uniform and concentric case neck than the previously mentioned method of reducing neck wall thickness, reaming.

Some cartridges may require fireforming to produce their final shape before neck turning or reaming can be performed properly. The only safe method we can recommend for this operation, is fireforming cases with an inert filler. For detailed instructions on this method of fireforming cases, see Ken Howell's Designing and Forming Custom Cartridges for Rifles and Handguns.

If you have further questions, please feel free to contact our tech line (607) 753-3331

The concentricity, or neck runout, of loaded cartridges is an important consideration for reloaders and especially the varmint or target shooter.

There are many factors that can cause or contribute to neck runout during the reloading process and many reloaders who have not dealt with the problem before quickly blame the sizing or seating die.

While the dies may be at fault or have a contributing defect, modern CNC machinery and reamers that cut the body, shoulder, and neck simultaneously make such occurrences rare. Most problems are related to the brass itself and its uniformity both in terms of hardness and thickness and how much it is being stressed in the reloading process.

An entire book can be devoted to this subject, but the amount of stress the brass is subjected to can be your key to finding a problem. If you "feel" any difficulty and /or heavy resistance when resizing your cases this can be a telltale clue.

Excessive difficulty while resizing can indicate any of the following: Poor choice of case lube, failing to clean the die and/or brass, faulty polish inside die, chamber large or at maximum S.A.A.M.I. spec resulting in excessive brass resizing. A large neck diameter in the chamber combined with brass that is thin or excessively turned can cause crooked necks in a hurry. The more brass has to be moved the more its residual memory takes over.

Resistance to pulling your cases over the size button can indicate problems. A "squawk" says "shame on you", you forgot to brush the residue out of the necks. A hard drag can indicate that the top of the size button is not smooth. Don't be afraid to polish the top radius with #600 wet paper, but don't reduce the outside diameter or you can create an excessive bullet fit. Carbide size buttons are now an option also; they have a lower coeffecient of friction.

We have conducted many tests over the years on the various factors contributing to concentricity problems with bottleneck cases. We have repeatedly found a definite correlation between the uniformity of the brass (or lack of it) and the resulting concentricity of the neck to the body of the case.

An interesting experiment also revealed that neck turning of brass that was intentionally sorted as non-uniform, showed little or no concentricity improvement when used in standard S.A.A.M.I. spec chambers. Conversely brass that was sorted and selected for uniformity remained uniform and concentric with or without a neck turning operation.

Another interesting observation can be found in the examination of fired cases that have crooked necks "as fired" right out of the chamber. Usually the chamber is being blamed for the problem.

Looking at the primers under magnification you can usually find a telltale machining mark or other blemish that was imprinted from the bolt face. This will give you an index mark with reference to the chamber. Mark this index mark on the cases with a felt tip marker and go about checking the concentricity. If the runout is random to your index marks the problem is not the chamber. Further examination will show the same correlation with the good and bad brass.

Note that to this point we have not talked about seating dies. That is because 98% of all concentricity problems exist in the brass prior to bullet seating.

Keep in mind that no seating die ever made will correct problems. The best you can do is to obtain a quality seating die that does not add any.

UPDATE: Feb. '96

Redding has now introduced neck sizing dies that use interchangeable sizing bushings in .001" increments. These dies can help reduce overworking of the brass and the resulting loss of concentricity.

If you have further questions, please feel free to contact our tech line below.

Headspace is one of those concepts that is both very simple and yet is extremely important to achieve gilt edged accuracy. For bottlenecked cartridges, headspace is simply the distance between the head of the cartridge case (the end where the primer is inserted) and the front/face of the firearm's bolt when the case's shoulder is positioned against the front of the chamber.

Headspace is one of those concepts that is both very simple and yet is extremely important to achieve gilt edged accuracy. For bottlenecked cartridges, headspace is simply the distance between the head of the cartridge case (the end where the primer is inserted) and the front/face of the firearm's bolt when the case's shoulder is positioned against the front of the chamber.

Firearms manufacturers have a problem in that the chambers in their guns have to be long enough to accommodate all of the cartridges of a given kind made by literally hundreds of manufacturers from around the world - all of which will vary slightly in length due to normal manufacturing tolerances. Consequently a certain amount of "slop" is built into the length of chamber to accommodate those differences. However, that slop can reduce accuracy.

The goal of every conciencious reloader should be to use proven and practical reloading proscedures in order to ensure that the bullet/case combination is as perfectly aligned with the center of the bore as possible. The more centered up the cartridge, the more accuracy we can expect. However, if the cartridge is laying loose in the bottom of the chamber because of a generous headspace dimension, it's obvious that the bullet will be pointed closer to the bottom of the bore rather than the center. Consequently, accuracy conscious shooters will want to reduce headspace to the absolute minimum i.e. where the shoulder of the case is against the front of the chamber wall and the bolt/breech face of the firearm is very close to or even lightly touching the head of the case. We can do this by adjusting the shoulder of our fired cases in the sizing process. However be aware that when we do so, we're customizing those cases to a precise fit in one particular gun. This means that those cases will probably fit only in that gun and in no other.

Headspace is like Goldilocks porridge. It has to be just right for the best accuracy. Too much is bad and too little is also bad. So how do we know when we have too much headspace? There are a couple of obvious tell tale signs on our fired cases that are sure fire indicators. The first is a protruding primer. If, after firing, you see the primer is backed out of the primer pocket, even a little bit, you have excessive headspace. Remember, the top of the primer in an unfired case is supposed to be located just below the case head after it has been seated. If it's sticking out after the shot has been fired, the case is too loose in the chamber.

The second indication of too much headspace is a excessively stretched case. When the powder is ignited, the case is expanding in all directions, including front and rear. Brass does have a limited amount of "springback", but when the amount of headspace exceeds the ability of the case to springback, the case will be permanently stretched and weakened. Stretched cases can be easily identified by a bright, light colored ring located just forward of the head. The case at that point has been stretched dangerously thin. Those cases should be thrown away immediately as they will come apart at that point sooner or later. Case head separations can sometimes be very nasty.

The ideal amount of headspace for the best accuracy is zero. In other words, all space behind the case head has been eliminated. When the bolt face is just touching the case head or is just, behind the case head, two good things are happening. One - the cartridge is aligned as well in the chamber as is possible. Two - when the firing pin hits the primer, the case will not be able to slide forward under the impact and will stay firmly in place. Consequently, the full force of the firing pin's blow will be delivered against the primer cup insuring efficient ignition. However, there is such a thing as going too far in our efforts to eliminate excess headspace.

One problem that many shooters using hard recoiling cartridges experience occurs when the headspace is less than zero. In other words, a hot load is stretching the case lengthwise to the point that if the case is just neck sized, it'll be a difficult fit in the chamber. In such cases, the shoulder has been moved so far forward that the bolt handle either won't go down or it will go down only with some degree of difficulty. These cases can also be identified by scrape marks on the head as a result of the bolt face rubbing that area under pressure as its being turned. You might also see brass scrapings on the bolt face itself. The cartridge is actually being inserted into the chamber with a crush fit. Under those circumstances, case life will be significantly reduced - especially primer pockets.

One way we can achieve an ideal headspace with these cases with shoulders that are too far forward is by adjusting our resizing die so that the case's shoulder is moved back to the ideal headspace location. To do so, raise the ram of your reloading press to the top position with the shellholder installed. Take your full length sizing die and screw it down to the point where it's touching the shellholder. Now back off the die by about a half turn. Run a lightly lubricated fired case into the die, and then try chambering it in your gun. If the case does not chamber, or chambers only with difficulty, screw the die down just a bit more (1/8th turn) and size the case again and rechamber. Keep repeating this procedure until the bolt on your gun just closes freely or as I prefer, with a very slight bit of resistance. Now lock the die in place. This is the classic method for adjusting headspace.

A good alternative is to use Redding's Competition Shellholder Kit. The kit is composed of five thicker* than normal shellholderswhich are packaged together in a neat little plastic case. A normal shellholder is .125" thick. The five competition shellholders are thicker* in increments of two thousandths of an inch i.e. +.002", +004", +.006", +.008", and +.010". Each shellholder is stamped with its increase in depth, and they are Black Oxide coated so they can't be confused with a regular .125" shellholder.

Using them is very easy. Start with the +.010" shellholder. Install on the press's ram and raise to the top position. Screw down the sizing die to the point that it's making firm contact with the shellholder. When that happens, the die is now being "squared" or aligned with the shellholder.

Lock the die in place. OK, take a fired, lubed case and run it into the die and then try chambering it into your gun. If it doesn't chamber, go to the +.008" shellholder and repeat the "squaring", resizing, and chambering procedure. Keep repeating until the case chambers easily. Cases sized with that shellholder now have the optimum headspace for the best case alignment.

One last note. If you size more than one type of case with these shellholders, keep a record of what shellholder to use for which cases. Also if you switch case brands, or even case lots, double check to see if the shellholder and die setting is still good. Differences in brass thickness and brass hardness can make a difference. This also applies sometimes even if you switch brands of lubricant. Strange but true.

Once you have your case's headspace squared away, you can be assurred that the chamber fit of your reloaded ammo will be "just right". Goldilocks would be proud.

*( Editor"s Note: the shellholders are actually the same thickness but the seat on which the case rests is machined deeper into the body of the shellholder giving the mechanical effect of a shellholder which would be thicker from the casehead to the top of the shellholder where it contacts the base of the die. By using this method, there is no need to readjust the die between the 5 different shellholders to accomplish the desired shoulder set back.)

Most hunters and many other shooters seeking smooth chambering reloads, full length size their cases each time. Since the interior dimensions of sizing dies are determined by the manufacturer, adjusting the shoulder setback is the only control a reloader has over how much a fired case is sized.

In the past, sizing die adjustment has been made through the trial and error method of rotating the die body in the reloading press. While acceptable results can be obtained using this method, precise adjustments are difficult at best.

Using this method, firm contact with the shellholder was not always possible. As a result, irregularities in brass hardness and thickness, as well as the uniformity and quantity of case lube affected shoulder setback. The resulting headspace variations created can adversely affect accuracy due to non-uniform primer/powder ignition. "Squaring" the die in the press is also precluded with this method of die adjustment.

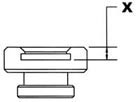

To provide desirable shellholder-to-die contact during sizing, without excessively setting the case shoulder back, Redding now offers shellholders that are in increments of .002" thicker than the industry standard. The nominal thickness for industry standard shellholders is .125". (See dimension X on the shellholder diagram.) Our new Competition Shellholder Set includes five shellholders that are thicker than this in increments of .002". Therefore, the set includes shellholders that are marked +.002, +.004, +.006, +.008 and +.010, which is the amount the shellholder will decrease case to chamber headspace.

To provide desirable shellholder-to-die contact during sizing, without excessively setting the case shoulder back, Redding now offers shellholders that are in increments of .002" thicker than the industry standard. The nominal thickness for industry standard shellholders is .125". (See dimension X on the shellholder diagram.) Our new Competition Shellholder Set includes five shellholders that are thicker than this in increments of .002". Therefore, the set includes shellholders that are marked +.002, +.004, +.006, +.008 and +.010, which is the amount the shellholder will decrease case to chamber headspace.

To select the proper shellholder for your particular firearm's chamber, start with the shellholder marked +.010. The shellholder should be adjusted to make firm contact with the bottom of the sizing die during the case sizing operation. Resize a case and try it (unprimed and empty) in the chamber of your firearm. If the empty case does not chamber or chambers with difficulty, switch to the shellholder marked +.008 and repeat the process. Stop at the shellholder that allows the firearm's action to close freely. Your cases are now being sized properly to fit your chamber with a minimum amount of headspace.